Ypres 2006

Poets, Airmen and Adolf

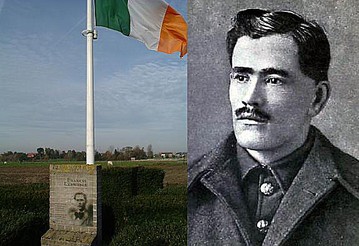

Gerry's Irish blood made him keen to visit one of the men of Ireland who died in the Great War, he was also a great poet. Francis Edward Ledwidge was born on 19th August 1887 and was from

County Meath.

Ledwidge was a keen patriot and nationalist. His efforts to found a branch of the

Gaelic League

in Slane were thwarted by members of the local council. The area organiser encouraged him to continue his struggle, but Francis gave up. He did manage to act as a founding member with his brother

Joseph of the Slane Branch of the

Irish Volunteers

(1914), a nationalist force sworn to defend the introduction of

Home Rule

for Ireland, by force if need be. On the outbreak of

World War I

in August 1914, and on account of

Ireland's involvement

in the war, the Irish Volunteers split into two factions, the

National Volunteers

who supported

John Redmond's

appeal to join

Irish regiments

in support of the

Allied

war cause and those who did not. Francis was originally of the latter party.

Nevertheless, having defended this position strongly at a local authority meeting, he enlisted (24 October 1914) in Lord Dunsany’s regiment, joining 5th battalion

Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers,

part of the

10th (Irish) Division.

This was against the urgings of Dunsany who opposed his enlistment and had offered him a stipend to support him if he stayed away from the war. Some have speculated that he went to war because his

sweetheart Ellie Vaughey had jilted him, but Ledwidge himself wrote, and forcefully, that he could not stand aside while others sought to defend Ireland's freedom.

Ledwidge seems to have fitted into Army life well, and rapidly achieved promotion to

lance corporal.

In 1915, he saw action at

Suvla Bay

in the

Dardanelles,

where he suffered severe

rheumatism.

Having survived huge losses sustained by his company in the

Battle of Gallipoli,

he became ill after a back injury on a tough mountain journey in

Serbia

(December 1915), a locale which inspired a number of poems.

Ledwidge was dismayed by the news of the

Easter Rising,

and was

court-martialled

and demoted for overstaying his home leave and being drunk in uniform (May 1916). He gained and lost stripes over a period in

Derry

(he was a corporal when the introduction to his first book was written), and then, returned to the front, received back his lance corporal's stripe one last time in January 1917 when posted to

the

Western Front,

joining 1st Battalion, Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers, part of

29th Division.

On 31 July 1917, a group from Ledwidge’s battalion of the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers was road-laying in preparation for an assault during the

Third Battle of Ypres,

near the village of

Boezinge

northwest of

Ypres.

While Ledwidge was drinking tea in a mud hole with his comrades, a shell exploded alongside, killing the poet and five others. A chaplain who knew him, Father Devas, arrived soon after, and recorded

"Ledwidge killed, blown to bits."

The poems Ledwidge wrote on active service revealed his pride at being a soldier, as he believed, in the service of Ireland. He wondered whether he would find a soldier's death. The dead were buried

at Carrefour de Rose, and later re-interred in the nearby

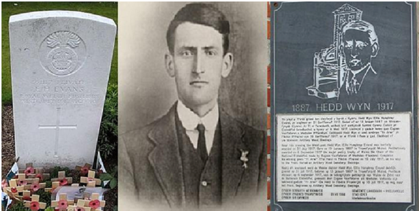

Artillery Wood Military Cemetery,

Boezinge, It is also where the Welsh poet

Hedd Wyn,

killed on the same day, is buried. You can read about Hedd below and see his memorial that we visited at Hagebos (Iron Cross)

Hedd Wyn (born Ellis Humphrey Evans) was a

Welsh language

poet

who was killed during the Battle of

Passchendaele. He was born on 13 January 1887 in Pen Lan,

a house in the middle of Trawsfynydd, Meirionydd, Wales.

He was the eldest of eleven children born to Evan and Mary Evans. In the spring of 1887, the family moved to the isolated hill-farm of Yr Ysgwrn, a few miles from Trawsfynydd (the village, today is more

famous for having a Nuclear Power Station).

In June 1917, Hedd Wyn joined the 15th Battalion Royal Welch Fusiliers at Fléchin, France. His arrival depressed him, as exemplified in his quote, "Heavy weather, heavy soul, and heavy heart. That is an uncomfortable trinity,

isn’t it?" Nevertheless at Fléchin he finished his National Eisteddfod entry and signed it “Fleur de

Lis”. It was sent via the

Royal

Mail on 15 July 1917.

That same day, the 15th Battalion marched towards the major offensive which would become known as the Battle of

Passchendaele. The attack began on 31 July 1917 at

3:50 a.m. Heavy rain turned the battlefield into a swamp. The 15th Battalion captured Pilckem Ridge and then advanced towards the "Iron Cross" stronghold, coming under heavy artillery and machinegun

fire.

In a 1975 interview conducted by St Fagans National History Museum, Simon Jones, a veteran of the Royal Welch Fusiliers, recalled," We started over Canal Bank at Ypres, and he was killed half way across

Pilckem. I've heard many say that they were with Hedd Wyn and this and that, well I was with him... I saw him fall and I can say that it was a nose cap shell in his stomach that killed him. You could

tell that... He was going in front of me, and I saw him fall on his knees and grab two fistfuls of dirt... He was dying, of course... There were stretcher bearers coming up behind us, you see. There

was nothing - well, you'd be breaking the rules if you went to help someone who was injured when you were in an attack."

Soon after being wounded, Hedd Wyn was carried to a first-aid post. Still conscious, he asked the doctor "Do you think I will live?" though it was clear that he had little chance of surviving.

Private Ellis Evans died at about 11:00 a.m.

Earlier this year BBC News did a piece on Hedd Wyn and the Welsh at Hagebos. You can read more and watch the piece by using the link below.

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-wales-21439931

Erich Maria Remarque’s “All quiet on the Western front” shows

the horrors of war and the waste of youth. And as we walked through the stone gateway to one of the few German cemeteries in the area at the huge and stark, Langemark was an area where 40,000 Germans lost their lives in a single battle,

3,000 of them being students not yet 18. Some who are buried in the mass graves between the slabs, bearing endless rows of names, includes those of the Student Battalion of "All Quiet on the

Western Front"

The cemetery, which evolved from a small group of graves from 1915, has seen numerous changes and extensions. It was dedicated in 1932. Close to the entrance is the comrades’ grave, which contains

24,917 servicemen, including the Ace Werner Voss. Between the oak trees, next to this mass grave, are another 10,143 soldiers (including 2 British soldiers killed in 1918). The 3,000 school students who were killed

during the First Battle of Ypres are buried in a third part of the cemetery.

The bronze statue of the four figures in this cemetery was created by the Munich sculptor Professor Emil Krieger, the statue is known as The statue of the Mourning Soldiers his inspiration was a

photograph of soldiers from the Reserve-Infantry-Regiment 238. The photograph was taken in 1918 as the soldiers mourned at the grave of a comrade.

This became a well-known photograph which appeared in the German press during 1918.The names of hundreds of those known to be buried in the cemetery but not in identifiable graves were at that time

carved on oak panels in a room on one side of the entrance building.

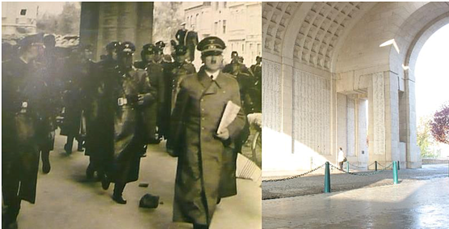

In June 1940, with fighting still going on around the Dunkirk perimeter, Hitler toured the battlefields of Flanders where he had served in WWI.

On 1 June he passed though Ypres (Ieper), where he drove through the town and visited the Menin Gate, the war memorial built by the British in the 1920s. He also visited the German cemetery at

Langemark, where a famous battle had taken place in October 1914.

We stumbled on a pub in Langemark, The Hotel Munchenhof. A cracking pub that even had inside a full sized 10 pin bowling alley. Obviously it would be rude not to have a go. The rest of the NMBS called me a ringer! but we had a few games, pints and a wind-down, as with all our tours its the hidden little gems that we find by accident or surprises that are usually the best. Then after that outside the pub was a frites (Chippy) van. Really beware of Belgiums bearing Mayonnaise, the cover your chips in it. I am not quoting a Pulp Fiction moment, but they smoother your chips in it, so always ask for a little!

Kevin, bless him loves WWI aces. Indeed, I would go so far to say that WWI fighter aces are Kevin’s favourite part of WWI. So to go and see Georges Guynemer’s memorial at Poelkappelle was

something he was keen to do.

On 8th June 1915 he joined his first and only operational unit, Escadrille MS3. This would later change its title to Spa 3, as French units were numbered according to the aircraft they were using.

The unit was part of the Cigognes - The Storks - and carried an emblem on their aircraft as can be seen on the monument at Poelkapelle.

His first aircraft was named Vieux Charles (Old Charles) and Guynemer stuck with it throughout all the planes he would fly. On the morning of 11 September 1917 Guynemer took of in company of

Lieutenant Bozon-Verduraz to patrol the area around Langemark (The Battle for the Menin Road would take place on the 20th - Part of 3rd Ypres, Passchendaele).

Mystery and intrigue surround his death. About 09:30 hours whilst flying at 4,000 metres over Poelkapelle, Guynemer spotted a German biplane and dived steeply to escalate the

dogfight.

As he was doing so eight German Albatross fighters arrived on the scene and made to intercept the Frenchmen.Bozon-Verduraz broke off realising that they were outnumbered and thought his squadron

commander had as well. Returning to base there he found no sign of Guynemer.

There was a great deal of controversy and ambiguity surrounding Guynemer's last moments. For many months, the French population refused to believe he was dead, rumours circulated that he had been

captured or had come down over the sea. It would appear that one way or another Guynemer had in fact been shot down.

Later investigations showed that German Infantry reached the crash site and identified Guynemer from his papers. Whilst Guynemer had been hit a number of times, a head wound was put down as the

official cause of his death.

No sooner had all this happened than the German Infantry had to take cover from a British barrage on the area which as part of the build up to the offensive would last until the 20th and destroyed

both pilot and aircraft. Guynemer's body was never found.